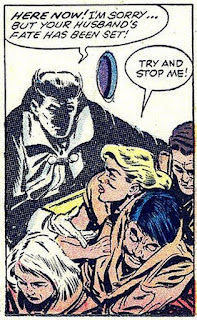

Researching the Man in Black in Toonopedia.com, I see that only his incarnation in the 1950s and '60s is mentioned, and his history from the 1940s is not. It is true that they seem to be two characters with the same name and appearance, both drawn by Bob Powell and his studio. The Man in Black (also called Fate, or Kismet) of the 1950s (see the link below) is a character who observes people at that moment when they have arrived at a fork in the road, and are deciding which one to take. The character we are showing today is also called Mr Twilight, or Death. In this incarnation he guides the spirits of the recently deceased to an afterlife. The afterlife is even referred to in one panel as Valhalla, although it doesn’t sound, from Mr Twilight’s description, to be the Viking Valhalla.

There is a bad guy, Dr Hideki, who is obviously Japanese, but the story was published in 1947, and the late unpleasantness of war against the Japanese is not mentioned. People die, and Dr Hideki brings 'em back to life. In this story we are supposed to root for them to die and be taken to their reward by Mr Twilight. If it sounds confusing...well, I guess it is. If anything, it probably isn’t a standard comic book plot. It is beautifully illustrated by Powell, who did his usual superb job, no matter how screwball the story.

From Green Hornet Fights Crime #34 (1947):

As promised, here is the Man in Black from 1957. Just click on the thumbnail.

Translate

Monday, April 18, 2016

Friday, April 15, 2016

Number 1880: The secret of the old tower

“The Old Tower’s Secret.” from Adventures Into the Unknown #2 (1949) gives the appearance of a triangle love story. Older husband, younger wife and younger man. And the husband lets the two go off together for the day. When he thinks the worst has transpired with the young people, events are set in motion that will haunt them (literally) a hundred years later. Things are not as we were led to believe.

Frank Belknap Long, who had a long career as a writer and was a contemporary and friend of H.P. Lovecraft, wrote the story, as well as the other contents of the first two issues of Adventures Into the Unknown. Edmond Good, a Canadian artist who came to the United States after World War II, contributed several stories to ACG and editor Richard E. Hughes over the years. Good, a member of the art colony in Woodstock, New York, was also the first artist for DC’s Tomahawk.

In this posting from 2011, after a mystical tale by Ogden Whitney, a space story by Edmond Good. Just click on the thumbnail.

Frank Belknap Long, who had a long career as a writer and was a contemporary and friend of H.P. Lovecraft, wrote the story, as well as the other contents of the first two issues of Adventures Into the Unknown. Edmond Good, a Canadian artist who came to the United States after World War II, contributed several stories to ACG and editor Richard E. Hughes over the years. Good, a member of the art colony in Woodstock, New York, was also the first artist for DC’s Tomahawk.

In this posting from 2011, after a mystical tale by Ogden Whitney, a space story by Edmond Good. Just click on the thumbnail.

Wednesday, April 13, 2016

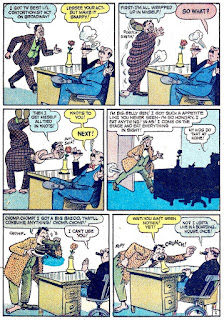

Number 1879: Suzie the chorus girl

The dumb blonde stereotype goes back quite a ways, long before Suzie was introduced in Top-Notch Laugh Comics #28 (1942), but was well established when she was awarded her own series. Suzie #50 (1945), from which this story is taken, is actually the second issue. At this time she was presented as being a young adult; later on in the series she became a teenager, right out of high school.

In this story, a broad comedy which bounces off the walls with ideas and story points not going directly to the main plot, Suzie gets a job from “Mr. Goldwater,” a talent agent. That inside joke is a reference to John Goldwater, one of the three founders of MLJ Comics, which became Archie Comics, publisher of Suzie.

Al Fagaly, a journeyman comic book man, is credited with the drawing, combining some of his faux Jimmy Hatlo (They’ll Do It Every Time newspaper comic panel) style. Later on Fagaly partnered with MLJ editor and writer Harry Shorten to do a knockoff of Hatlo’s successful panel, called There Oughta Be a Law for the McClure Newspaper Syndicate. Here is a link to examples of the Shorten/Fagaly collaboration from Hairy Green Eyeball in 2009, including one of the panels with an idea submitted by Basil Wolverton.

In this story, a broad comedy which bounces off the walls with ideas and story points not going directly to the main plot, Suzie gets a job from “Mr. Goldwater,” a talent agent. That inside joke is a reference to John Goldwater, one of the three founders of MLJ Comics, which became Archie Comics, publisher of Suzie.

Al Fagaly, a journeyman comic book man, is credited with the drawing, combining some of his faux Jimmy Hatlo (They’ll Do It Every Time newspaper comic panel) style. Later on Fagaly partnered with MLJ editor and writer Harry Shorten to do a knockoff of Hatlo’s successful panel, called There Oughta Be a Law for the McClure Newspaper Syndicate. Here is a link to examples of the Shorten/Fagaly collaboration from Hairy Green Eyeball in 2009, including one of the panels with an idea submitted by Basil Wolverton.

Monday, April 11, 2016

Number 1878: The Fantom and the Big Robot

Any information I have on the Fantom of the Fair comes from an informative entry in Don Markstein’s Toonopedia website. Quickly, though, the Fantom is one of the very first non-DC superheroes to appear in comic books (Amazing Mystery Funnies Vol. 2 No. 7, July 1939) after Superman...Fantom was never shown with a secret identity, no origin story, no reason given for doing what he did...lived in a lab under the New York World’s Fair, protected Fairgoers. Later he was renamed Fantoman and earned his own short-lived comic book, but then Centaur went out of business and it was goodbye to the guy. He was probably created by Paul Gustavson, who went on to a prolific career in comics of the forties.

Today I have a story of the Fantom protecting those Fairgoers from a giant robot. And really, that is almost my sole reason for showing it. Historic or not, in my mind the Fantom is secondary to a huge, clanking, stomping, havoc-wreaking mechanical man. Paul Gustavson gets the byline for drawing (and probably writing), and Frank Thomas gets the honors for drawing the dramatic cover.

From Amazing Mystery Funnies Vol. 2 No. 11 (1939):

Today I have a story of the Fantom protecting those Fairgoers from a giant robot. And really, that is almost my sole reason for showing it. Historic or not, in my mind the Fantom is secondary to a huge, clanking, stomping, havoc-wreaking mechanical man. Paul Gustavson gets the byline for drawing (and probably writing), and Frank Thomas gets the honors for drawing the dramatic cover.

From Amazing Mystery Funnies Vol. 2 No. 11 (1939):

Friday, April 08, 2016

Number 1877: Hang 'em low

As is true of many Western outlaws and gunmen, some of the tales that have grown up around Texan Bill Longley are exaggerated and false. Longley was a murderer, an army deserter, and all-around bad guy, but he was not saved from a lynch mob hanging by a stray bullet splitting the rope, as shown in this story from Desperado #1 (1948). I have said several times that “true” is a floating concept in crime comic books, and when matched up with legends, the legends usually take over. Much more visual, you know.

Longley killed people, but his own boastful nature, inflating his misdeeds, probably helped do him in. He was eventually sentenced to hang. The detail missing from the comic book version is more gruesome than anything shown. The gallows were built, but the sheriff miscalculated how long the rope needed to be. Bad Bill, a six-footer, hit the ground, then was dragged up and strangled by the noose. It took 11 minutes before a doctor could pronounce him dead.

The 1948 version, drawn by Fred Guardineer, was published decades before the eventual true outcome of Bill Longley’s story. His grave was located and his remains confirmed by DNA testing in 2001. That part of the story, with the science involved, is taken for granted by us nowadays, but in Bill Longley’s day would have been wilder and more improbable than any of the stories told about this Texan badman.

Longley killed people, but his own boastful nature, inflating his misdeeds, probably helped do him in. He was eventually sentenced to hang. The detail missing from the comic book version is more gruesome than anything shown. The gallows were built, but the sheriff miscalculated how long the rope needed to be. Bad Bill, a six-footer, hit the ground, then was dragged up and strangled by the noose. It took 11 minutes before a doctor could pronounce him dead.

The 1948 version, drawn by Fred Guardineer, was published decades before the eventual true outcome of Bill Longley’s story. His grave was located and his remains confirmed by DNA testing in 2001. That part of the story, with the science involved, is taken for granted by us nowadays, but in Bill Longley’s day would have been wilder and more improbable than any of the stories told about this Texan badman.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)