The tentacled monstrosity looks inspired by H.G. Wells' The War Of the Worlds, the pyramid-shaped UFO goes against the stereotype of the flying saucer, popular at the time in science fiction comics. It makes one think of ancient aliens, especially when the monster tells Airboy it's their second visit to Earth. The planet is much more developed than the first time, when “your Earth was no danger to us.” Holy Erich Von Däniken!*

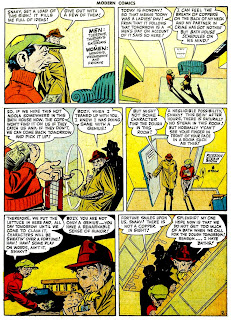

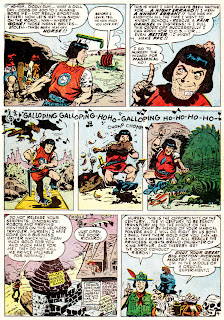

From Airboy Comics Volume 9 Number 6 (1952), art by Ernie Schroeder:

*Chariots of the Gods, 1968.

**********

Since many of the creators of comic books were Jewish, there are parallels to be drawn to a people, a religion, and superheroes. Superman creators Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster certainly fit the description since Superman, above all others, lifted the comics industry “up, up and away,” and in its early years into the stratosphere of popularity. And they did it with a character who, according to Rick Bowers in his book, Superman Versus the Ku Klux Klan, had Jewish attributes.

From the book:

“Jerry and Joe’s Jewish heritage deeply influenced the makeup of Superman too. The all-American superhero reflected many of the beliefs and values of Jewish immigrants of the day. Like them, Superman had come to America from a foreign world. Like them, he longed to fit into to his strange new surrounding. Superman also seemed to embody the Jewish principle of tzedakah — a command to serve the less fortunate and to stand up for the weak and exploited – and the concept of tikkun olam, the mandate to do good works (literally to ‘repair a broken world’). Even the language of Superman had Jewish origins. Before Superman is blasted off the dying planet of Krypton, Superman’s father, Jor-El, names his son Kal-El. In ancient Hebrew the suffix El means ‘all that is God.’”Bowers goes on to compare the Superman story to Moses, especially the “crib-shaped rocket” launched toward earth “to be raised by loving strangers.” In the Old Testament Moses’ mother, after Pharaoh’s decree that all newborn Jewish males be killed, puts Moses in a crib-shaped basket and puts him in the Nile. He is raised by Pharaoh’s daughter. Bowers ends by further comparing Superman to the story of Rabbi Maharal of Prague, “who created his own superman, called the Golem, to protect the people of the Jewish ghetto from hostile Christians.”

Superman was also a secular American product. As was the custom, obvious religion or ethnicity was avoided. Bowers mentions Siegel’s love of science fiction, reading pulps like Amazing Stories, The Shadow, Doc Savage, and the novel, Gladiator by Philip Wylie. In that book a father creates a superhuman in his son. There were a whole lot of influences on Siegel and Shuster as Superman came haltingly to life over a period of years. At one point he was even a villain.

The Superman backstory is setup to the point of the book, the story arc from The Adventures of Superman radio program of the late forties, which involved Superman fighting a Ku Klux Klan-type organization.

Bowers gives a history of the Ku Klux Klan and its political power in the early decades of the Twentieth Century. In 1946, with the Adventures of Superman program riding high in the ratings the advertising agency for the show’s sponsor, Kellogg’s, suggested the program do shows about intolerance. (Fresh in the public minds were images from the Nazi death camps.) Producer Robert Maxwell “jumped at the chance,” according to Bowers. But it was a jump carefully taken. The producers reportedly read 25 scripts they rejected, but finally settled on former New York Times reporter, then freelancer, Ben Peter Freeman, to do the writing. He had written some very successful scripts for the program, and he was tapped to do the job on “Operation Intolerance.”

There’s some information in the book on Josette Frank, who was listed prominently for years in DC Comics as a member of the Child Study Association of America. Although such experts as Frank were dismissed as flacks by comic book critics like Fredric Wertham, Frank did have some input into what DC was doing. (She was a critic of Wonder Woman and the bondage themes of that comic, for instance.) She arranged a meeting between Bob Maxwell and anthropologist Margaret Mead who, according to Bowers, “advised Maxwell to step carefully with – as the agenda put it – ‘stories dramatizing, realistically or by allegory, the fight against threats to democracy – fascism, intolerance, mob run, vigilante movements,’” as Mead said might be “inappropriate to the building of serene attitudes.” Maxwell’s response was, “What makes you think there is any serenity in children’s programming?”

And that debate is still with us nearly 70 years later.

Superman Versus the Ku Klux Klan is an interesting blend of comic book, radio, and American history of the first half of the Twentieth Century. Bowers has done his homework. I find his tie-ins with Jewish culture and popular culture especially interesting. Run out of Europe, Jews came to the United States and founded movie studios and publishing empires. They even set the course of comedy on television. When we talk about what is “American” we include what has been assimilated, folded into American society from other cultures, now so well accepted we often forget origins.

Superman Versus the Ku Klux Klan by Rick Bowers. National Geographic Books, 2012. Hardbound, 160 pages. $18.95.

— Pappy