The quirky, oddball art of Fletcher Hanks is covered in two excellent Fantagraphics books by Paul Karasik: I Shall Destroy All the Civilized Planets! and You Shall Die By Your Own Evil Creation! Karasik did research on the man himself, and gives us a bio of Hanks as an alcoholic with a mean streak who deserted his family. I think his personality disorders and addictive dependencies figured into his work.

Fantomah (by “Barclay Flagg”) is one of his creations. He apparently wrote, drew and lettered his own comics, so they had a singular vision. Fantomah dispenses justice in the jungle, and in this story to a couple of white hunters out to loot a jungle city of gold. Fantomah is magic, and her head turns into a skull when she goes to work on the crooks. (That is a unique characteristic, although The later Ghost Rider from Marvel comes to mind.) Hanks used tracings. He would repeat poses. When he got a drawing he liked he found it economical to trace it off and re-use it in the same story, sometimes on the same page.

I also noticed his writing. In this story, from Jungle Comics #3 (1940) the final panel is anti-climactic.

[SPOILER ALERT] The villains, who are spared by Fantomah after being transformed into giant green insect creatures, have a bland reaction: “Crime doesn’t seem to pay.” “You’re right.” I wonder if they considered how they would be perceived when they landed their plane and stepped out in their new bodies. Once done with the story Hanks just wrote finis without thinking of it beyond the final panel, except maybe how Fantomah was going to defeat the “wild legions of beast-men” in the next issue, as promised in the final caption.

Talented cartoonist Eric Haven has done a pastiche of Hanks in “Bed Man” — which not only captures Hanks’s absurdism, but also manages to one-up him. You can see it by clicking on the thumbnail:

Friday, January 29, 2016

Wednesday, January 27, 2016

Number 1846: The Saint and Ann Brewster

I wish more was known about artist Ann Brewster. She worked in comics in the forties and fifties, beginning in the Jack Binder shop. From the examples I have seen of her work, includng this Saint story from The Saint #5 (1949), she was an excellent artist, working in several genres, science fiction, mystery, even inking the incredible Frankenstein for Classics Illustrated #26 (first printing 1945). Women who worked in the early comic books are rare, but there are a few and their work is notable.

The Saint is a creation of Leslie Charteris, pseudonym of Leslie Charles Bowyer-Yin, born in Singapore in 1907 to a Chinese father and English mother. His famous literary creation, Simon Templar, aka the Saint, was introduced in 1928, and Charteris wrote 50 of the novels. In 1963 he turned over the job to others. Charteris died in 1993 at age 85; the Saint novels are still available.

The Saint in comic book was not as long-lived as the character in novels, appearing in 12 issues from Avon in the forties. As with the newspaper comic strip originally drawn by Mike Roy and then John Spranger, Charteris had a personal involvement and exacting standards. I believe Ann Brewster’s handsome rendition of the character would have met with Charteris’s approval.

Another Saint story from this issue, this one drawn by Warren Kremer. Click on the thumbnail.

The Saint is a creation of Leslie Charteris, pseudonym of Leslie Charles Bowyer-Yin, born in Singapore in 1907 to a Chinese father and English mother. His famous literary creation, Simon Templar, aka the Saint, was introduced in 1928, and Charteris wrote 50 of the novels. In 1963 he turned over the job to others. Charteris died in 1993 at age 85; the Saint novels are still available.

The Saint in comic book was not as long-lived as the character in novels, appearing in 12 issues from Avon in the forties. As with the newspaper comic strip originally drawn by Mike Roy and then John Spranger, Charteris had a personal involvement and exacting standards. I believe Ann Brewster’s handsome rendition of the character would have met with Charteris’s approval.

Another Saint story from this issue, this one drawn by Warren Kremer. Click on the thumbnail.

Monday, January 25, 2016

Number 1845: Captain Midnight: Doom beam and other gimmicks

This story, from Captain Midnight #12, published in 1943, smack-dab in the middle of World War II, is full of gimmicks. Some of them outrageous (a “fluotian tablet” to put out large fires? We need that for the guys battling massive wildfires in the Western U.S. every summer.) At least one gimmick is real, the gliderchute outfit Captain Midnight uses to fly.

The least realistic is a “doom beam” that Captain Midnight uses to illuminate the enemy’s chest with a clock hand pointing to 12:00. Shades of the Hangman and his superimposed gallows! (See the link below).

The whole premise, evil angel Nazis who trade on the superstitions of ignorant natives, is visually exciting if improbable. There is also stereotyping of the South Americans, with one of them called Taco. For all that I enjoyed the story, which is yet another way of bringing in Nazis...by 1943 creative minds were having problems coming up with more sabotage plots for the enemies of America to use.

The Grand Comics Database gives “?” to all the creative team. To me the art looks like it comes from the Jack Binder shop.

From the very early days of this blog, the Hangman. Just click the thumbnail.

The least realistic is a “doom beam” that Captain Midnight uses to illuminate the enemy’s chest with a clock hand pointing to 12:00. Shades of the Hangman and his superimposed gallows! (See the link below).

The whole premise, evil angel Nazis who trade on the superstitions of ignorant natives, is visually exciting if improbable. There is also stereotyping of the South Americans, with one of them called Taco. For all that I enjoyed the story, which is yet another way of bringing in Nazis...by 1943 creative minds were having problems coming up with more sabotage plots for the enemies of America to use.

The Grand Comics Database gives “?” to all the creative team. To me the art looks like it comes from the Jack Binder shop.

From the very early days of this blog, the Hangman. Just click the thumbnail.

Friday, January 22, 2016

Number 1844: Television terror

Our family got a television in 1950, and the terror — television addiction — set in.

Okay, that is my story. The story you came here to see is from The Haunt of Fear #17 (actual #3), in 1950. “Television Terror!” was written and drawn by Harvey Kurtzman before he became an editor at EC Comics. I am presenting it in black line because the way it was drawn and inked it looks more like the black and white TV that was the standard of the television industry then and for years to come. It is also an example of the way early television was sometimes presented, as radio with pictures.

Okay, that is my story. The story you came here to see is from The Haunt of Fear #17 (actual #3), in 1950. “Television Terror!” was written and drawn by Harvey Kurtzman before he became an editor at EC Comics. I am presenting it in black line because the way it was drawn and inked it looks more like the black and white TV that was the standard of the television industry then and for years to come. It is also an example of the way early television was sometimes presented, as radio with pictures.

Wednesday, January 20, 2016

Number 1843: Ravin' for the Raven

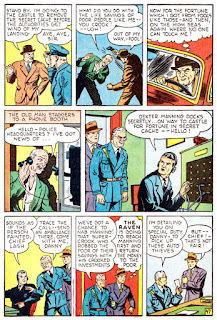

Dexter Manning is a 1941 millionaire, when a million was a real chunk of change. Dexter can afford a castle, a manservant, and yet keeps his wealth in cash. He plans to abscond with the swag but first he gives his manservant a .45 caliber retirement plan. No wonder Dexter has a bad reputation.

Enter the Raven. Unlike many costumed heroes with no superpowers, Raven is not a wealthy playboy. This so-called Robin Hood is a detective both masked and unmasked, who goes after evil one-percenters.

The story is from Ace’s Four Favorites #1 (1941), and is credited to Adolphe Barreaux. Barreaux is also known for his sexy Sally the Sleuth stories from Spicy Detective, one of DC's line of sexy pulp magazines. Barreaux is one of the earliest comic book artists, having done the Sally strip (and I do mean strip, since the girl could not keep her clothes on) since 1934. The Spicy line was kept separate from DC, and Barreaux ran his own art studio. Later he was editor of the Trojan line of comic books, yet another DC side business.

Enter the Raven. Unlike many costumed heroes with no superpowers, Raven is not a wealthy playboy. This so-called Robin Hood is a detective both masked and unmasked, who goes after evil one-percenters.

The story is from Ace’s Four Favorites #1 (1941), and is credited to Adolphe Barreaux. Barreaux is also known for his sexy Sally the Sleuth stories from Spicy Detective, one of DC's line of sexy pulp magazines. Barreaux is one of the earliest comic book artists, having done the Sally strip (and I do mean strip, since the girl could not keep her clothes on) since 1934. The Spicy line was kept separate from DC, and Barreaux ran his own art studio. Later he was editor of the Trojan line of comic books, yet another DC side business.